From Jack Van Kley, Van Kley & Walker, LLC December 21, 2016

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE ABOUT YOUR DRAINAGE RIGHTS:

Flooding from high stream flows or heavy unchanneled runoff from land can cause substantial damage to property. Disputes between neighbors can arise when a landowner on higher ground increases the volume or rate of flow onto another landowner’s property, or when a landowner on lower ground blocks the flow from another landowner’s higher land.

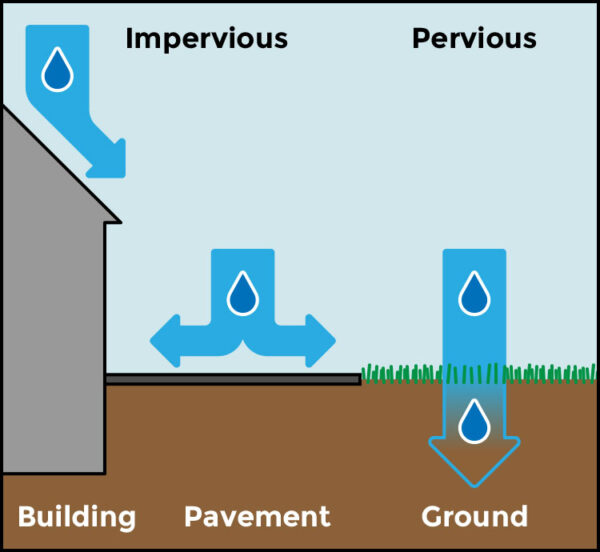

Drainage problems, and disputes over drainage problems, can occur on land that is used for any purpose. [n rural areas, drainage disputes can arise when one farmer’s fields are flooded by rainfall or snow melt flowing off another farmer’s fields, or when poor drainage on one farmer’s fields blocks effective drainage from another farmer’s fields. In urban areas, the construction of paved parking lots, buildings, roads, and other

impervious surfaces can prevent the percolation of precipitation into the soil and increase the storm water runoff onto adjoining properties. The increased storm water runoff can erode the soil and flood basements, yards, gardens, and septic systems.

This article explains the drainage rights possessed by Ohio landowners in the form of questions and answers. This information is applicable to drainage in all types of land use, whether industrial, commercial, residential, recreational, or agricultural. The references to “landowners” in these questions and answers also apply to renters and other persons who occupy a property.

True or False? An upper (uphill) landowner always has the right to drain all of his surface water onto a neighbor’s downgradient (downhill) land, regardless of the flow volume and the amount of damage it causes on downgradient land.

Answer: False. If the drainage causes an unreasonable amount of damage to downgradient land, then the upper landowner is liable for encroaching on the downgradient neighbor’s property rights. Ohio’s courts have adopted a “reasonable use” doctrine that the com1s use to determine whether a landowner’s drainage activities have violated another landowner’s property rights. This principle allows a landowner to develop or modify his prope11y in a manner that increases the drainage onto a neighbor’s land, but only if the increased drainage does not unreasonably interfere with the neighbor’s drainage. A project that interferes with drainage is unreasonable if its hann to other landowners outweighs the project’s benefits. This is a subjective standard that is based on fairness and common sense.

This balancing test evaluates the following facts to determine the seriousness of harn1 to the landowners adversely affected by the interference with drainage:

- the extent of the harm;

- the character of the harm;

- the social value of the use or enjoyment that is harmed;

(d) the suitability of the damaged use or enjoyment to the character of the locality; and

(e) the burden on the hanned landowner if she has to fund and implement the actions necessa1y to avoid ham1 from the other landowner’s drainage.

This balancing test evaluates the following facts to evaluate the value of the project that interferes with drainage:

(a) the project’s social value;

(b the project’s suitability to the character of the locality;

- whether it is impracticable to prevent or avoid the interference; and

- whether it is impracticable to maintain the project if its owner is required to bear the cost of compensating for the interference with drainage.

A judge or jury will use these factors to compare the seriousness of the harm caused by the project with the project’s value to determine whether the project unreasonably interferes with drainage. Generally, a landowner’s interference with another landowner’s drainage will be found unreasonable if most citizens would find the interference to be unfair or offensive.

True or False? An upper landowner is allowed to increase his drainage onto a neighbor’s land even if the higher volume of drainage exceeds the highest flows that have historically occurred from her land.

Answer: True, as long as the increased flow is reasonable as determined by the balancing test described in the previous answer.

True or False? An upper landowner can always increase the speed of surface water flow onto downgradient land without liability as long as the total volume of water does not increase.

Answer: False. Even if an upper landowner does not increase the overall amount of water drained onto a neighbor’s land, the upper landowner is liable if he accelerates the speed of drainage in a manner that unreasonably floods or interferes with drainage on his neighbor’s land.

True or False? If surface water has historically flowed in a stream or over the ground surface from a landowner’s land onto someone else’s land, the landowner has an unlimited right to increase the flow even if it harms a neighbor’s property.

Answer: False. Even if the route of a flow has existed for centuries, an increase in flow is governed by the reasonable use doctrine. The upper landowner can increase the flow, but only if it is reasonable.

True or False? A landowner is not allowed to construct developments (such as buildings or parking lots) or make other unnatural changes to his land that increase the surface water flow onto neighboring land that is greater than the land’s natural flow.

Answer: False. A landowner is allowed to develop his land in any manner that does not cause an unreasonable interference with the drainage of other landowners, even if the increased flow exceeds historic levels. However, the landowner is liable if the increased flow unreasonably damages the downgradient landowner.

True or False? A landowner can be liable for interfering with a neighbor’s drainage even if she takes no purposeful action to interfere with the flow.

Answer: Trne. If conditions on a landowner’s property interfere with a neighbor’s drainage, the landowner can be liable for the drainage interference even if she did not intend to interfere with the neighbor’s drainage.

True or False? If vegetation or debris plugs a tile or pipe on a downgradient landowner’s land and floods an upper landowner’s land, the downgradient landowner can be liable for the damage even though the downgradient landowner took no action to plug the tile or pipe.

Answer: True. The downgradient landowner is required to properly maintain his tiles and pipes to allow proper drainage on the upper property. However, if vegetation or debris flowing from the upper landowner’s property clogs the downgradient landowner’s tile or pipe, the upper landowner may be responsible for the problem.

True or False? A landowner is allowed to dig a trench in a marsh or other wetland to improve the drainage on his land.

Answer: False. Generally a landowner is prohibited from digging, filling, or moving soil in a wetland for any purpose, unless the landowner has a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and/or the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency. Protected wetlands include marshes, swamps, bogs, and similar areas that possess saturated soil.

Some woodlands are wetlands if they are saturated during a portion of the year, even if they are dry for the rest of the year. Before clearing or digging in a saturated area, it is important to find out whether it is a wetland.

True or False? A downgradient landowner has an absolute right to prevent an upper landowner from discharging surface water onto the land of the downgradient landowner by erecting a wall or taking other action to block the flow.

Answer: False. An upper landowner has the right to discharge surface water on downgradient land, as long as the flow is reasonable. The downgradient landowner cam1ot block this flow so long as it is reasonable. However, the downgradient landowner can take reasonable action to reduce the flow if necessary to protect the downgradient landowner’s land from unreasonable damage.

True or False? Under some circumstances, a downgradient landowner is allowed to interfere with the natural flow of surface water from an upper landowner’s land even though it causes some harm to the upper landowner’s property.

Answer: True. A downgradient landowner is allowed to restrict the flow from upper land if the interference is reasonable.

True or False? If a tile, ditch, or other drainage structure on downgradient land deteriorates and impairs an upper landowner’s drainage due to no fault of the downgradient landowner, the downgradient landowner is required to repair the structure at his own expense.

Answer: Generally true, unless the upper landowner has entered into an agreement or easement with the downgradient landowner agreeing to pay for or share the expense. For another exception to this principle, see the next question and answer.

True or False? A landowner can defray the expense of improving or restoring the effective drainage of her land by initiating action requiring other landowners to share in the expense if their lands also benefit from the improved drainage.

Answer: True. A landowner can submit a petition to the county commissioners to initiate proceedings for constructing, modifying, repairing, or maintaining ditches, dams, reservoirs, walls, tiles, and other drainage or flood control structures. If the county commissioners detennine that a project is necessary, feasible, and cost-effective, they have the authority to approve, fund, and construct it. The costs of the project are assessed to the benefitting landowners in proportion to their benefits, whether or not they supported the petition. Petitions also can be submitted to the local Soil and Water Conservation District, which evaluates and approves the projects and then refers the projects to the county commissioners for ultimate approval and implementation.

True or False? Ohio has enacted a state law that establishes a landowner’s drainage rights.

Answer: False. Ohio has no state law that provides a landowner with the right to drain surface water from the landowner’s land, nor does state law prohibit ;;;omeone from discharging surface water on a landowner’s land. For that reason, no state agency has the authority to stop someone from violating a landowner’s drainage rights. However, the Supreme Com1 of Ohio has established the reasonable use doctrine for drainage that is described above. This doctrine enables landowners to file private lawsuits to enforce their drainage rights against persons who unreasonably damage their property.

Ohio does have a law that prohibits a person from obstructing the drainage in watercourses and ditches along public highways. The purpose of this law is to prevent the highways from flooding, but keeping these drainage ways open also benefits adjoining landowners.

Some counties, townships, or municipalities have enacted laws that govern drainage. These laws may provide local government with limited authority to address drainage issues.

True or False? Richland County has enacted laws regulating all drainage activities in the county.

Answer: False. State law authorizes counties to regulate drainage on some types of property, but not on other types. For example. state law does not authorize counties to regulate drainage on land used by public utilities, railroads, and agriculture. Counties cannot regulate drainage on crop fields or other agricultural land. In addition, the county

does not have authority over drainage activities inside the City of Mansfield and some other municipalities.

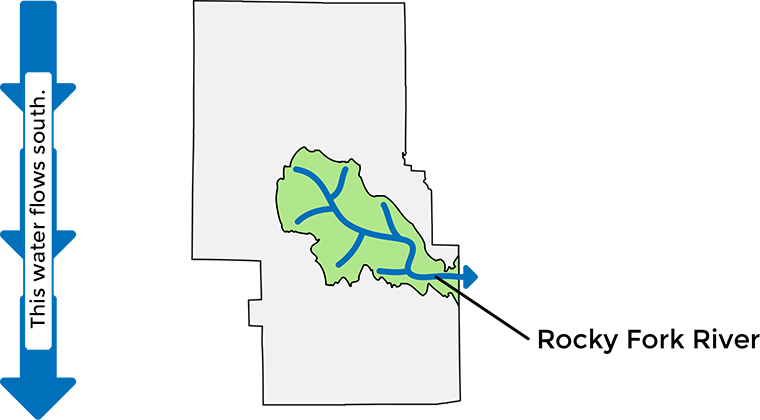

The Richland County Board of Commissioners does have the authority to regulate, and does regulate, surface and subsurface drainage from the construction of single-family, two-family, and three-family dwellings and any other building or structure that disturbs at least 3,000 square feet of soil, creates at least 2,000 square feet of impervious surface, or disturbs soil within 100 feet of a stream, a wetland, or Special Flood Hazard Area. The Richland County Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD) administers these drainage requirements for the county commissioners.

Any person who develops a regulated project must install an effective drainage system to prevent drainage problems. Permits issued by the county identify the drainage controls that must be installed and operated. A person may change the pre-existing surface or subsurface drainage on the developed property, but only to the extent that these changes do not flood or saturate upgradient or downgradient properties or otherwise harm any person or property.

Article VII of the county’s Stormwater Management and Sediment Regulations provides additional details about these requirements. A copy of these regulations can be found on this web site at this link [install link].

True or False? The Richland County Board of Commissioners and the Richland County Soil and Water Conservation District (S\VCD) have the authority to decide disputes between landowners over drainage issues.

Answer: Generally false. State law limits the county’s jurisdiction over drainage. The county commissioners have only the authority to enforce Article VII of the Stom1water Management and Sediment Regulations against anyone who is causing a drainage problem in violation of those regulations. Any other drainage issue is not subject to county authority.

The SWCD is not an enforcement agency, but we assist the county commissioners with technical advice in implementing and enforcing these regulations. In addition, the SWCD can provide landowners with technical advice to help them solve their drainage

problems if they are willing to work with us. The article at this link [install link] provides you with additional infonnation about how we can help.

This article has been prepared by Jack A. Van Kley of the law firm of Van Kley & Walker, LLC, 132 Northwoods Boulevard, Suite C-1, Columbus, OH 43235. Mr. Van Kley can be contacted at (614) 43 t-8900. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of this publication, it is not intended to provide legal advice as individual situations will differ and should be discussed with a lawyer. Reading this article does not create an attorney-client relationship between the author and the reader.

Knowing Your Water Rights

Here are additional questions and answers about water rights. Since there are a fair number of them, you may wish to create a new page for them.

I. What are the rights of the public to use a stream (such as a river or creek) or lake?

Answer: The public has the right to use any navigable stream or lake for boating and fishing. The public has no right to use a navigable stream or lake for swimming, wading, bathing, hunting, or other purposes unless the owner of the bed of the stream or bed has agreed to allow that access. The public has no right to use non-navigable streams or lakes for any purpose without the permission of the landowner.

- How can I tell whether a stream or lake is navigable?

Answer: A stream is generally navigable if canoes or other boats can navigate it under natural conditions and if it is accessible from publicly owned land. A lake on private property is unlikely to be classified as navigable even if canoes or other boats can navigate it, unless the lake is of great size.

- Does the public have the right to go onto private property in order to reach a navigable stream or lake?

Answer: No, that would be a trespass on the landowner’s land. The public must use publicly owned land to reach the navigable water or obtain a private landowner’s permission to use her land for that purpose.

- Does the public have the right to walk on the bank of a navigable stream or lake?

Answer: The bank is not part of a navigable stream or lake. A person has no right to walk on the bank, fish from the bank, or do anything else on the bank unless he owns the bank or has been given the landowner’s pennission to use it. The public can use the bank if it is on government property (such as a park or wildlife refuge) and the governmental owner has provided access to the public.

- Does the public have the right to fish, wade in, or engage in any other activity in a non-navigable stream, lake, or pond if the water is accessible from public property?

Answer: A person has the right to use a non-navigable stream, lake, or pond only if she owns it or has been given permission by the owner to use it.

- If a person owns land under a stream or lake, for what purposes can he use the stream or lake?

Answer: A person who owns the bed of a stream or lake, or any part of it, can use the water in the stream or lake for boating, fishing, irrigation, swimming, drinking, and other purposes. His use of the water must be conducted in a reasonable manner that does not deprive other owners of their rights to use and enjoy the water. For example, one landowner is not allowed to use so much water for irrigation or other purposes that other landowners are unable to boat on it. Ohio courts have not provided clear direction on whether the owner of part of the bed of a privately owned lake has a right of access to the entire lake for boating and other purposes, or has access to only the portion that he owns. A landowner’s rights can be affected by easements, covenants, or contracts that restrict or enlarge her rights to use a stream or lake.

- If a landowner’s land is separated from a stream or lake by someone else’s land, does the landowner have a right to use the water?

Answer: A landowner whose land is separated from a lake or stream by any other person’s land has no more right to use the lake or stream than any other member of the public.

- Can the government stop my neighbor from taking too much water and drying up my well, lake, or stream’?

Answer: No. Government agencies have no authority to restrict the amount of water pumped from a lake or stream. However, Ohio law does authorize a landowner to file a lawsuit to protect the landowner’s own water supply.

This article has been prepared by Jack A. Van Kley of the law firm of Van Kley & Walker, LLC, 132 Northwoods Boulevard, Suite C-1, Columbus, OH 43235. Mr. Van Kley can be contacted at (614) 431-8900. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of this publication, it is not intended to provide legal advice as individual situations will differ and should be discussed with a lawyer. Reading this article does not create an attorney-client relationship between the author and the reader.