The easiest and most immediate step you can take towards healthy soil is mulching. Learn how!

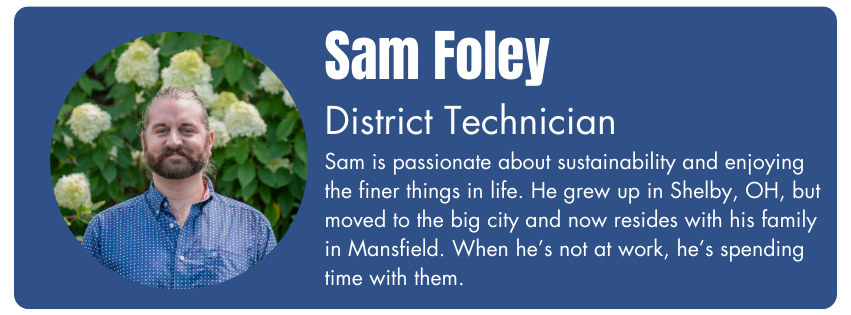

By Sam Foley

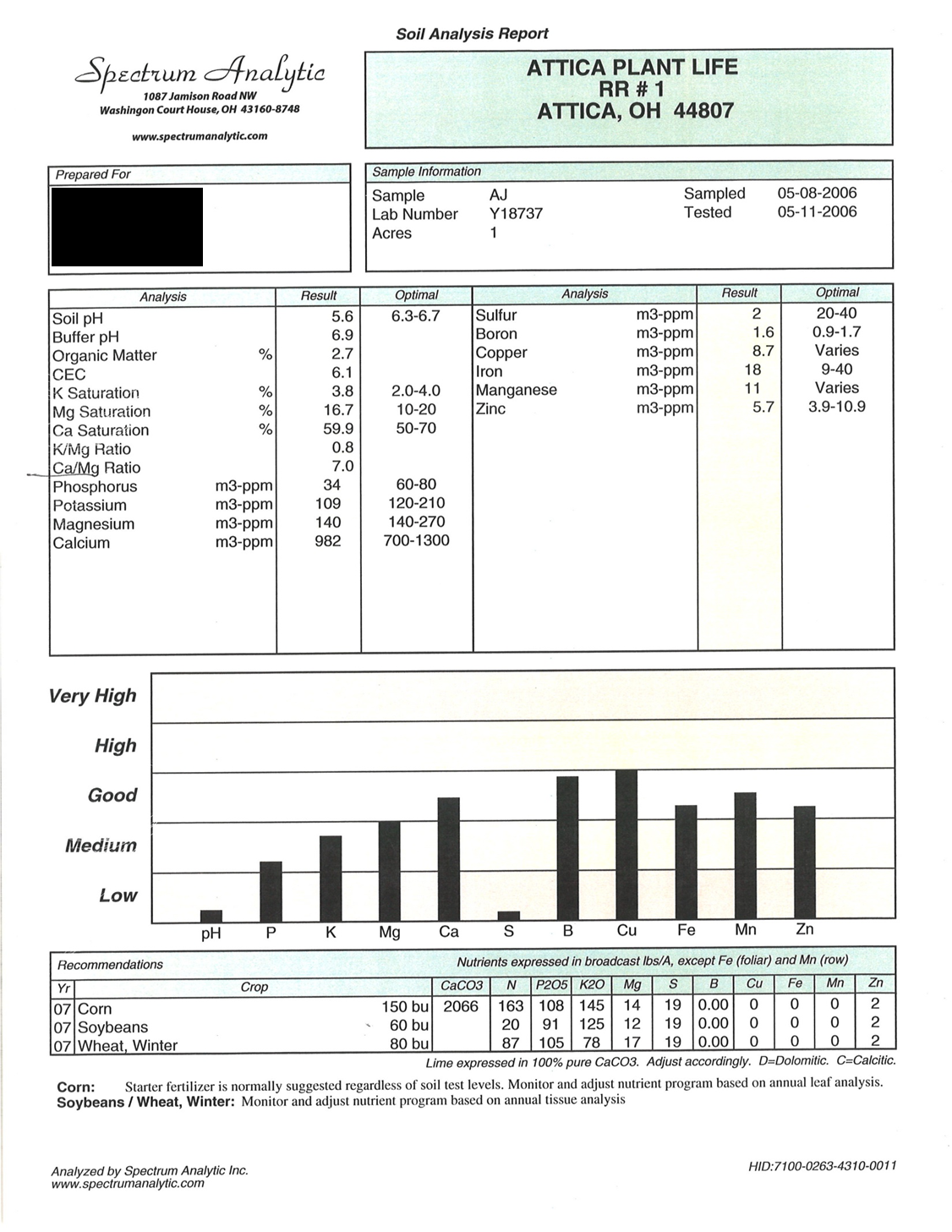

I’m going to let the audience in on a secret today; I’m incredibly passionate about healthy soil. I love talking to folks about their soil test results and discussing ideas to increase soil health. The easiest and most immediate step you can take towards healthy soil is mulching. The benefits a mulch layer can add to your garden are listed below:

- Preventing soil erosion: By covering the top layer of soil there’s greater protection from erosion during watering and rain events.

- Retaining moisture: Mulch helps lock in moisture after watering and prevents rapid evaporation. This also helps combat drought.

- Controls temperature: Protects the soil during times of extreme weather. Beneficial for both winter and the hot summers. This can be especially helpful in raised beds.

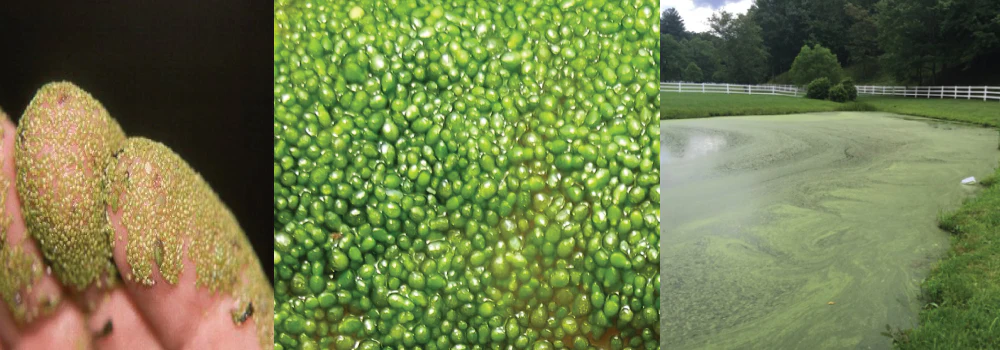

- Microbes: This extra protection for the top layer of soil increases microbe activity, which in turn, greatly impacts soil health and productivity. Find the microbial activity in your soil by taking the Soil Your Undies Challenge.

- Weed suppression: Though it’s not 100% effective, mulch greatly reduces weed pressure and makes pulling what weeds do pop up that much easier. Most weeds spread by seed, and a few inches of mulch can prevent these seeds from even making it to the soil.

Mulch can be made of almost any material and is simply a cover spread over top of our growing media to enrich and insulate that media. My favorite mulches are organic options. Several examples of commonly used organic mulch are compost, leaf litter, straw, grass clippings, shredded bark, and rice hulls. Another option could be a living mulch. This could be made up of cover crops or even herbs, that grow as companions to a target crop. Living mulch can be “chopped and dropped”, cut and laid on the surface of soil, providing an additional layer of cover. Organic mulch not only provides the traditional benefits of mulch, but it also adds nutrients back into the soil as it slowly breaks down over time. This is a regenerative solution that can help build up soil health year after year.

Soil in your garden should never be left bare. Keeping soil covered with mulch and cover crops is essential to soil health. Always maintain a layer and leave mulch in place year-round. If you’re looking for guidance or just want to chat about growing, please reach out to me! Stay tuned for future articles on gardening.